February 3 アニー・マーフィー・ポールの『パーソナリティーのカルト――いかにパーソナリティー・テストが私たちに誤った子供の教育をさせ、誤った会社の経営・・・』 Annie Murphy Paul, The Cult of Personality: How Personality Tests Are Leading Us to Miseducate Our Children, Mismanage Our Companies, and Misunderstand Ourselves (2004) [擬似科学周辺]

February 03, 2009 (Tuesday)

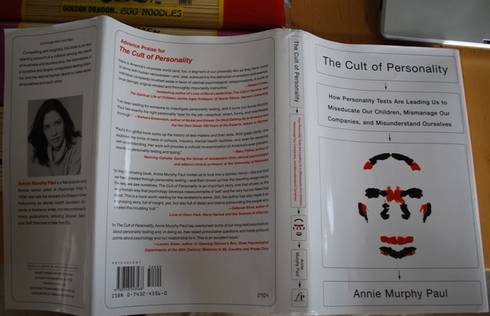

この日アマゾンを通して届いた本。『パーソナリティーのカルト』

Annie Murphy Paul, The Cult of Personality: How Personality Tests Are Leading Us to Miseducate Our Children, Mismanage Our Companies, and Misunderstand Ourselves (New York: Free Press, 2004) xv + 303pp. ISBN:0743243560

副題が長い。おかげでブログのタイトル欄ににおさまりませんでした。カバー装丁はちょっとおしゃれだと思いますが。「いかにパーソナリティー・テストが私たちに誤った子供の教育をさせ、誤った会社の経営をさせ、誤った自己理解をさせるか」

著者のアニーさんはイェール大学を卒業して『サイコロジー・トゥデー Psychology Today』誌の編集をつとめたあと現在はフリーランスで『ディスカヴァー Discover』、『サロン Salon』、『セルフ Self』、『レイディーズ・ホーム・ジャーナル Ladies' Home Journal』などに寄稿してきたニューヨーク在住の女性ライターです。『シェイプ Shape』では "Mind/Body" という毎月のコラムを担当しているみたい。

主眼は現在のアメリカの状況にあるのでしょうけれど、歴史的に人格・パーソナリティー検査のもろもろが語られていて、第1章 "A Most Typical American" は骨相学を扱い 、第2章 "Rorschach's Dream" はロールシャッハ、第3章 "Minnesota Normals" は1930年代におこった Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)、第4章 "Deep Diving" は Henry Murray の Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)、第5章 "First Love" は1940年代にペンシルヴェニアの主婦が考案した Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)、第6章 "Child's Play" は Draw-a-Person Test (DAP)、第7章 "The Stranger" は Raymond Cattell の Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)、そして第8章 "Uncharted Way" 、Epilogue というのが本文(リンクは英語のWikipediaの記事)。ふつうは本の冒頭に置かれるAcknowledgement がそのあと2ページにわたってあって、229ページから291ページまで注がついています。あと索引Index も10ページ。タイトルの付け方とか、ジャーナリスティックですし、文体もくだけた読み物的な感じですけど、詳しい典拠を示す注とかは学術的な気配をそこはかとなく漂わせています。

第1章だけ読めばよかったのですが(爆)。―

第1章の「最も典型的なアメリカ人」というのは詩人のウォルト・ホイットマンのことで、30歳になって2ヶ月ほどたった1849年7月16日にマンハッタンのナッソー・ストリートにあるファウラー・アンド・ウェルズの事務所を訪ねるところの物語的記述からこの章は始まっています。

第2段落から――

Entering an examining room, he [Walt Whitman] took a seat before the man he'd come to see. Lorenzo Niles Fowler had serious eyes, an impressive beard, and an air of calm authority; with practical skill he began running his fingers over the young man's head. A stenographer sat close by, recording his every word.

"Combativeness, six," Fowler pronounced. "Secretiveness, three . . . Self-exteem, six to seven . . . Conscientiousness, six . . . Mirthfulness, five"―on and on, more than three dozen scores in all.

The young man paid his three dollars and stepped back out into the bustle of Nassau Street. Though he might have looked the same to the merchants and newspapermen hurrying past, he knew he was profoundly changed. At last he'd been seen for who he was, and proof was in the report tucked under his arm. "You are one of the most friendly men in the world and your happiness is greatly depending on your social relations," Fowler had written. "You are familiar and open in your intercourse with others but you do not by so doing lose your dignity.

"You are no hypocrite but are plainspoken and are what you appear to be at all times . . . You have your own opinions and think for yourself . . . Your sense of justice, of right and wrong is strong . . . You are a great reader and have a good memory of facts and events . . . You can compare, illustrate, discriminate, and criticize with much ability . . . You have a good command of language especially if excited."

It was an uncannily accurate description of the young Walt Whitman, and Whitman took from it both reassurance and inspiration. The American Bard, the Great Gray Poet who would go on to write "Song of Myself," "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd," and "O Captain! My Captain!" had found an unlikely muse―in phrenology.

Phrenology, or the "science of mind," was a wildly popular way for nineteenth-century Americans to understand themselves and others. Lorenzo Fowler and his brother, Orson, were its leading proponents in this country, and they taught their legions of followers that every human attribute sprang from a particular structure of the brain. When well used, these organs would expand, pushing up the skull just above to produce a palpable bulge. By feeling a person's head, the expert phrenologist could read its rugged topology like a map of what lay within.

The Fowler brothers and their partner, Samuel Wells, identified a total of thirt-seven faculties, from Cautiousness to Intuitiveness, Destructiveness to Benevolence, each with a corresponding bump rated in size from one to seven. They called many of these traits by unusual or invented names: "Adhesiveness" indicated one's capacity for devotion and commitment; "amativeness" described the proclivity to feel amorous and sexual; "alimentiveness" was their term for a love of food and drink.

They had no more faithful student than Whitman. He spent hours at the Fowler & Wells Phrenological Cabinet, wandering among its ghostly heads. (The cabinet, a kind of museum, displayed nearly a thousand plaster casts of such notable specimens as savages, murderers, and madmen.) He read and underlined phrenological trancts, copying passages into his journal. He even wrote about the practice himself, extolling its virtues in the pages of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. "Breasting the waves of detraction as a ship dashes sea-waves, Phrenology, it must now be confessed by all men who have open eyes, has at last gained a position, and a firm one, among the sciences," he proclaimed.

The Fowlers repaid his devotion with generous patronage, making Whitman a staff writer on one of their many periodicals. When in 1855 he self-published his first book, Leaves of Grass, they sold it at their shop; when a second edition came out, Fowler & Wells was its publisher. Bound into each volume was Whitman's "chart of bumps," which he regarded as a credential, evidence of his claim to be a new kind of poet and a new kind of man. Flattering though his reading had been, Whitman saw room for improvement and augmented several of his scores. (He also wrote rhapsodic, and anonymous, reviews of his own work: "An American bard at last!" he raved in The United States Review.)

The phrenologists' early appreciation of his gifts gave Whitman the confidence to pursue his bold project of creating a truly American literature. But the concepts and vocabulary of phrenology also imbued the poetry itself. "In America," he jotted in his notes, "an immense number of new words are needed." Whitman found these words in the phrenologists' catalogue of human qualities and used them to sing of himself:

Never offering others, always offering himself, corroborating

his phrenology

Voluptuous, inhabitive, combative, conscientious, alimentive,

intuitive, of copious friendship, sublimity, firmness, self-esteem . . .

いまのところ、とりあえず抜き書きだけしておきます。いろいろ他にも面白い記述があり、いろいろ思うところもあるのですが。

コメント 0